When Are Feeding Tubes Given to Children

Feeding Tubes & Gastrostomies in Children

- Overview

- Other Names

- Billing & Coding

- Clinical Practice Guidelines

- Feeding Tubes

- Oral Feeding vs. Tube Feeding

- Indications for a Feeding Tube

- NG- and NJ -Tubes

- G-tubes & GJ-tubes

- Ostomy Care

- Role of the Medical Home

- Resources

Overview

This resource discusses non-surgical and surgical feeding tubes, their differences, how they are placed, and common issues encountered in children with special health care needs. These include nasogastric (NG), gastrostomies (G-tube or button), nasojejunal (NJ), and gastro-jejunal (GJ) (also known as gastro-enteral) tubes. Tubes used less commonly, such as gastro-duodenal and orogastric tubes, are not discussed.

Other Names

Enteral feeding

Gastro-enteral tube

Gastro-jejunostomy or GJ-tube

Gastrostomy or G-tube

Nasoduodenal or ND-tube

Nasogastric or NG-tube

Nasojejunal or NJ-tube

Orogastric or OG-tube

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy or PEG

Billing & Coding

ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Codes

P92.x Feeding problems of newborn

R63.3, Feeding difficulties (child >28 days)

Z93.1, Gastrostomy status

Z43.1, Encounter for attention to gastrostomy

Z46.59, Encounter for fitting and adjustment of other gastrointestinal appliance and device (e.g., replacement of nasogastric tube)

Z97.8, Presence of other specified device (e.g., nasogastric feeding tube)

ICD-10-PCS Procedure Codes

F0FZ2FZ, Caregiver training in feeding and eating using assistive, adaptive, supportive, or protective equipment

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Adams RC, Elias ER.

Nonoral feeding for children and youth with developmental or acquired disabilities.

Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):e1745-62. [Adams: 2014]

This clinical report provides (1) an overview of clinical issues in children who have developmental or acquired disabilities that may prompt a need to consider nonoral feedings, (2) a systematic way to support the child and family in clinical decisions related to initiating nonoral feeding, (3) information on surgical options that the family may need to consider in that decision-making process, and (4) pediatric guidance for ongoing care after initiation of nonoral feeding intervention, including care of the gastrostomy tube and skin site; American Academy of Pediatrics.

Irving SY, Rempel G, Lyman B, Sevilla WMA, Northington L, Guenter P.

Pediatric Nasogastric Tube Placement and Verification: Best Practice Recommendations From the NOVEL Project.

Nutr Clin Pract. 2018;33(6):921-927. [Irving: 2018]

This article provides consensus recommendations for best practices related to nasogastric tube location verification in pediatric patients. These consensus recommendations have been approved by the American Society for Parental and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) Board of Directors.

Feeding Tubes

Feeding tubes offer alternative ways for nutrition to enter the gastrointestinal system while bypassing the mouth and esophagus. Feeding tubes are used to help children who need additional help to gain weight, protect from complications from oral feeding, and ensure that the child receives enough fluids to stay adequately hydrated. (Intravenous nutrition, known as total parental nutrition (TPN), is not addressed here.) These tubes also provide options to give medications when a child cannot or will not take them by mouth. While feeding tubes are sometimes used by parents to vent gas or drain unwanted fluids from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, these practices can be more deleterious than helpful.

Differences among the various feeding tubes, gastrointestinal ostomies, and common concerns are addressed below. Decisions about placing and removing any tube that goes in the body can be difficult. It is important for families and medical personnel to discuss the benefits and possible risks associated with the various options before making a decision.

Oral Feeding vs. Tube Feeding

Feeding tubes are never considered "first-line" treatment. Indications for tubes are only considered after other routes of nutrition and/or hydration are not adequate to meet the child's needs. Teaching young children to feed themselves and eating together as a family are deeply ingrained social norms. As such, families often prefer oral feeding over tube feeding, even if it takes a long time and requires additional preparation. Parents may not think of tube feeding as "eating." [Petersen: 2006] For various reasons, including the "unnaturalness" of tube feeding and other psychosocial concerns, parents may persist with oral feeding despite stressful or unenjoyable mealtimes and instructions from a physician to provide nothing by mouth. [Sullivan: 2000] [Petersen: 2006] Even in the absence of malnutrition, some patients have Pediatric Feeding Disorder (PFD) defined as impaired oral intake that is not age-appropriate and associated with medical, nutritional feeding skill, and/or psychosocial dysfunction [Goday: 2019]; children with PFD may require feeding tubes for supplemental nutrition. Children with feeding or enteral tubes typically need multidisciplinary providers and home health medical team as well as increased psychosocial support for the family. [Edwards: 2016]

Preliminary research suggests that a well-managed feeding tube usually (but not invariably) has a positive impact on nutritional status, but little is known about the overall impact of a feeding tube on a child's or family's function long term. A systematic Cochrane review of gastrostomy tube feeding in children with CP does not support either tube or oral feeding over the long term; more study is needed. [Sleigh: 2004]

Indications for a Feeding Tube

Indications for a long-term or permanent feeding tube may include:

- Unsafe oral feeding. In some children, tube feeding may be necessary due to frequent coughing, choking, and aspiration. Even if maximum efforts are made to prevent aspiration of food and drink into the lungs (with gastrostomy tube feeding and less commonly, Nissen fundoplication), oral secretions may still be aspirated.

- A diagnosis of Pediatric Feeding Disorder and/or Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), often characterized as "extreme picky eating."

- Recurrent periods of dehydration or weight loss due to frequent illnesses

- The need for an alternate route to give medications, fluids, persistent anorexia, or an unpalatable diet (ketogenic diet formulas). If malnutrition is present, oral feeds, even with nutritional supplementation, are rarely enough to resolve it. Sometimes, however, a period of tube feeding (nasogastric or gastrostomy tube) supplementation may allow the child to catch up to a normal weight and then continue with oral feeds alone.

- Percutaneous or surgical placement of a gastrostomy tube is recommended if the child will require long-term tube feeding. Despite their long-term use, these tubes are readily removable when no longer necessary.

- The child with a feeding tube can be fed by tube at night, supporting overall growth and hydration while allowing hunger and thirst to occur during the day so that oral feeding can continue. This may also be a time that oral-motor skills improve and oral feeds may be optimized, allowing a better transition back to oral feeding.

NG- and NJ -Tubes

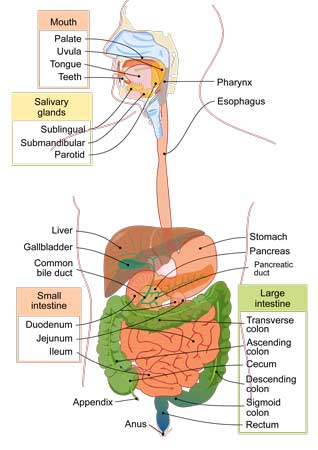

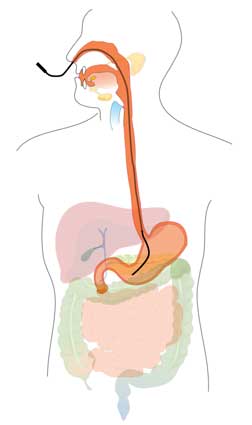

Nasogastric (NG) and nasojejunal (NJ) tubes are placed manually through the nose into the stomach or small intestine (image, right). These are generally used for relatively short-term management of feeding problems - typically days to several weeks. Orogastric (OG) tubes are sometimes used with complex choanal atresia patients or cleft patients in a hospital setting and are not discussed here.

NG-tubes are placed by passing a thin, flexible tube through a nostril, down the back of the throat through the esophagus, and into the stomach (see diagram below). Once placed in the medical setting, parents or caregivers can be taught how to replace the tubes at home, and they often become more comfortable doing this than the child's physician. The safest practice for determining the length of the NG-tube is to measure from the tip of the Nose, to the Ear, to the xyphoid process, and then to the Midline of the Umbilicus (the NEMU method) [Irving: 2018] and then marking this length on the tube that will be inserted.

The safest methods for NG-tube location verification include pH testing of gastric secretions (pH of 1–5.5 is indicative of correct placement) and radiography.

Safety alerts warn against the use of auscultation and visual inspection of gastric aspirate as means of NG location verification because either can give false affirmation. [Irving: 2018] Improper placement of NG-tubes can result in complications, including insertions into the esophagus, small intestine, pharynx, cranium, or respiratory tract (which can lead to aspiration), and perforations; deaths may result.

Liquid nutrition can be given through the NG feeds in larger intermittent amounts called boluses or over longer periods of continuous feeds (such as night feeds). Liquid nutrition can be delivered by gravity or with a pump, or pushed by syringe. Certain centers are exploring the benefits of NG-tubes to prepare infants to leave the neonatal intensive care setting and receive home tube feeding with close clinical follow-up. [White: 2020]

NJ tubes need to extend past the stomach into the small intestine. The first part of the small intestine is called the duodenum, and, ideally, the NJ tube extends past the duodenum to adequately deliver fluids beyond the stomach. For children who cannot have feedings into their stomachs, NJ tubes are often the next alternative. NJ feeds cannot be given as boluses; they require slower and longer feeding times (and are usually given by pump). One of the challenges to NJ tubes is that they can often curl up in the stomach unintentionally. NJ tubes are placed (and replaced) with the help of radiology, with an x-ray to confirm the placement is correct.

Both NG- and NJ-tubes can be easily dislodged or completely pulled out while a child is playing, moving around, or having care done. While the initial placement of a tube can make a child gag and feel uncomfortable, an NG or NJ tube is usually well-tolerated once the child becomes used to it. Other drawbacks include facial rashes from the adhesives on the face. Alternatives to facial adhesives include a bridle, which is a small piece of string that can anchor the tube behind the nasal bones and relieves the patient from irritating facial tape.

G-tubes & GJ-tubes

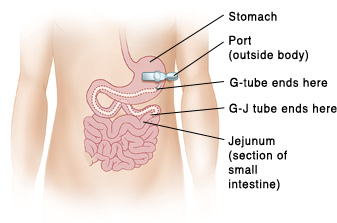

Ostomies generally refer to surgically created percutaneous pathways to enter or exit the body, such as a gastrostomy that is a pathway to the stomach, or a jejunostomy that is a pathway to the jejunum (part of the small intestine). A gastrostomy tube (G-tube) is a gastric feeding tube, passed through a gastrostomy, designed for liquid nutrients, fluids, or medication administration. Most of these procedures are now performed endoscopically or laparoscopically instead of as an open surgery.

In the procedure known as percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy or PEG-tube placement, a videoscope is passed through the mouth, down the esophagus, and into the stomach to guide the insertion of a tube through the abdominal wall accessing the stomach. PEG can be performed by a gastroenterologist or a surgeon. A temporary tube may be placed initially, and then later replaced with a low-profile or "button" device (with balloon or non-balloon internal bolsters). Gaining in popularity, laparoscopically assisted gastrostomy, or LAG-tube placement, can be performed by a surgeon and appears to be associated with fewer complications. [Sandberg: 2018] The site typically heals within 4 weeks

G-tubes are placed in children who tolerate feedings into the stomach but cannot orally consume enough calories to maintain adequate nutrition and growth. These children are at risk for aspiration of oral feedings due to difficulty with oropharyngeal control, esophageal motility, and/or gastroesophageal reflux. [Sleigh: 2004] G-tubes can be changed when leaking or approximately every 6 months, though there is no expert consensus on how often to change a functioning G-tube.

Many studies have focused on the use and safety of G-tubes. For example, improved weight gain after G-tube placement without serious complications was demonstrated in a 5-year retrospective study of children with neurological impairment, malnutrition, and oromotor dysfunction. [Dipasquale: 2018] Caregivers of children with a gastrostomy tube may spend up to 8 hours per day on care activities and experience high out-of-pocket expenses. [Heyman: 2004] Studies such as these give general insights into caring for a child with special health care needs; however, families and caregivers need to discuss the benefits and risks of tube placement and tailor their decision based on the child's unique circumstances.

There remains a lack of consensus on which infants should undergo G-tube placement. A recent study demonstrated no significant increase in hospitalizations or emergency room visits using an evidence-based oral-feeding protocol in infants and children <= 2 years old with oropharyngeal dysphagia and aspiration compared to those receiving feeds via G-tube. [McSweeney: 2020]

G-tube placement alternatives:

- Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) - endoscope or image-guided radiography to ensure proper G-tube placement

- [Percutaneous] laparoscopically assisted gastrostomy (LAG or PLAG) (e.g., Seldinger technique)

- Stamm gastrostomy - open surgical procedure, higher rate of complications

- Janeway gastrostomy - conventional laparoscopic procedure, higher rate of complications

- Percutaneous radiological gastrostomy (PRG) – Interventional radiology-guided push-pull non-endoscopic placement directly through the abdominal wall

G-tube Equipment

Many people use brand names to refer to their child's device, but the generic terminology for the 2 styles is "balloon" and "non-balloon." Common brand names include AMT MiniONE, MIC-KEY, and Bard. Ask for clarification if someone refers to a device that you are not familiar with.

|  |

Balloon-bolster low-profile gastrostomy device

- It contains an internal, water-filled balloon that holds the low-profile device in place and prohibits displacement.

- The balloon is breakable, so G-tube changes may be required more frequently than non-balloon devices.

- The valve is located on the outside of the body.

- It is relatively easy and painless to change.

- It has a feeding adapter locking mechanism.

Non-balloon button

- It contains a mushroomed-shaped tip which prevents displacement.

- The mushroom tip is less likely to break than the balloon tip, and therefore needs to be changed less frequently (once per year).

- The valve is located inside the stomach, making the non-balloon button less noticeable than the balloon device.

- It is more difficult to change and may require anesthesia to replace.

- It does not have a feeding adapter locking mechanism.

Feeding via a G-tube

- Care should be taken to select the appropriate formula. A consultation with local nutrition experts or pediatric gastroenterology may be helpful.

- Formula, approved blender diets, water, and liquid medications are the only fluids permissible through a G-tube. If a child uses thickeners to help reduce aspiration while drinking, the thickened fluids cannot be given through these tubes.

- The child should always be held upright during feeding.

- Oral stimulation (chewing, sucking on a pacifier) is recommended during the feed to promote a normal feeding environment and encourage regular stomach and intestinal motility.

- Participation at the dinner table and routine family eating activities should be performed during a G-tube feed to promote socialization.

- The G-tube should be flushed with water after each feeding to avoid obstruction due to drying of residual formula or medications. Recommended flushes are 5-10cc of water for infants and 15-30cc of water for older children.

- Most children who do not have a fundoplication repair should be able to burp and expel excess gas through their esophagus and mouth just like other children. If a child has neurologic delays or a fundoplication, venting can be done using an empty syringe, opening the extension catheter to drain air out, or with a specialized decompression tube for some buttons.

The gastrostomy-jejunostomy (GJ-tube) is an alternative for enteral feeding. It is most often placed to prevent aspiration or gastroesophageal reflux. It may be used to prevent the need for a fundoplication. [Onwubiko: 2017] A GJ-tube passes through the the stomach wall and then into the jejunum (2nd part of the small intestine), allowing fluids, nutrition, and medication to bypass the stomach if needed. The tube is held in place with a plastic disk on the outside of the abdomen and a balloon or plastic bumper on the inside of the stoma. There are 3 ports located externally: the G, the J, and the balloon. If a child has a G-tube already, it can be converted into a GJ-tube using interventional radiology rather than another surgery. The GJ option enables the care team to be selective about what enters the stomach, if anything. If a child receives all medications, fluids, and nutrition into the jejunum, the G portion still enables the stomach to be vented. Jejunal feeds must be given at a continuous rate by pump rather than as boluses (larger volumes given more quickly). Replacing a GJ is more technically difficult than replacing a G-tube and requires experienced medical personnel. Typically, GJ changes are scheduled every 3 months and often can be performed over a wire, thus minimizing fluoroscopy time. Unscheduled replacement of a dislodged GJ-tube can be more time-consuming.

Medication Safety

To prevent medical errors and improve patient safety, it is important to think about which medications, formulas, and supplements are given, how they are formulated (liquid versus pill, immediate-release formulations versus time-release, etc.), and how they are metabolized (processed) in different parts of the GI tract. All prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, supplements, and natural or holistic remedies need to be discussed with the medical provider and pharmacist to help prevent interactions. Some medications, including some liquids, require diluting before administering through a tube. Co-administered liquid medications can alter the pH and cause denaturing of either or both medicines. Medical errors can arise from crushing certain medications, mixing medications together for administration, or even mixing certain medications with nutritional formulas.

The tube may become clogged or deteriorate with exposure to certain chemicals and formulations. Viscous liquid medications may adhere to the interior of the tube, despite flushing. Immediate-release products are more likely to be able to be crushed and given by tube; however, the finer particle size caused by crushing can still change the drug's metabolism in the body.

Extended-release or enteric-coated pills, tablets, or capsules are not designed to be crushed and given through a feeding tube. Feeding tubes should be flushed between each medication. The site of administration needs to be considered as well. Medications given by mouth (oral route or "PO"), into the stomach (gastric route, via NG or GT), and into the small intestine (enteral route, via NJ, duodenal, or jejunal tubes) are not metabolized the same way. Certain medications, such as proton pump inhibitors, warfarin, and oral iron formulations are absorbed in the duodenum and should be given into the stomach rather than the jejunum. Pharmacists are trained to optimize use of medications and supplements, so it is important to consult a pharmacist directly.

Complications

Placement

- Major complications in a retrospective cohort of 208 patients with gastrostomy placement by interventional radiology included peritonitis (3%), [Dookhoo: 2016] and death (0.4%). [Friedman: 2004] Spearing or poking the transverse colon can occur, requiring surgery to fix.

- Minor complications in this cohort included tube dislodgement (37%), tube leakage (25%), and g-tube skin infection (25%). [Friedman: 2004]

- A review of 90 GJ-tubes placed at one center demonstrated complications in <20% and included one intestinal perforation. Although there were no procedural-related deaths, mortality was 23%, attributed in part to the underlying medical fragility. [Onwubiko: 2017] Another study identified risk of perforation at 9.4%, occurring most frequently in patients <10 kg, and mortality risk at 0.9%/person. [Morse: 2017]

Pulling out the G-tube

- Children can pull-out their g-tube directly or inadvertently through contact or traction while playing.

- Dressing children in a "onesie" (a one-piece undershirt with the tube tucked inside) or placing the end of the tubing under the tabs of a disposable diaper can help avoid the tube being pulled out.

- Using an abdominal binder can also protect the tube from being pulled out.

- A dislodged GJ-tube typically requires fluoroscopy to replace.

Commercial vendors include many businesses started by entrepreneurial parents who recognized the need for adaptive and protective clothing to protect privacy and prevent tubes from being pulled out. The Medical Home Portal does not endorse any of these products but offers the following as an example of these resources.

- Adaptations by Adrian is a commercial site offering sales of adaptive clothing, including onesies, sizes small child to 2XL adult.

Leaking

- Leaking is a common problem with feeding ostomies. Ensuring that the tube is properly placed and, if there is a balloon, it is properly inflated can reduce leaking.

- Balloon style buttons for children vary in the volume contained in the balloon. Typically, this is 3 mL (cc) for infants up to 1 year and 5 mL (cc) for older children. If unsure, contact the physician who placed the button.

- Other factors that may affect the tube's fit include granulation tissue, damaged or displaced tubes, or outgrowing the tube size after weight gain. Leaking may also occur if the stomach expands or becomes full of fluids or air. When children are sick and/or their stomach does not empty easily, tubes may be more prone to leakage.

Ostomy Care

The site where the gastrointestinal tract (stomach or intestine) is pulled up to meet the skin heals into an opening called a stoma. There are many other kinds of ostomies not covered in this section, such as colostomies and ileostomies as exits for chyme (digested food and fluid) or stool, tracheostomies for respiration, and urostomies for removal of urine. Stoma nurses (or enterostomal teams) have specialized experience in caring for common problems, such as irritation or leaking.

Bathing

- Parents should clamp the g-tube or close the valve prior to bathing the child.

- Avoid overly hot water, which could irritate the surrounding skin.

- Use mild soaps and soft washcloths to avoid further irritation and abrasion.

Granulation tissue

- Granulation tissue represents a normal foreign body reaction in the skin surrounding the tube. It is red/pinkish, inflamed epithelial tissue that is firmer and more fibrous, like scar tissue.

- Seeing a wound clinic or ostomy nurse can be helpful for controlling and identifying causes of granulation tissue. Tubes should never be "tacked down" to one side of the abdomen for longer than a few hours, as this tension may worsen the granulation tissue or cause subcutaneous infections. • Excess granulation tissue can be controlled or reduced by topical application of triamcinolone cream 3 times daily for a week or cauterization using silver nitrate sticks obtained through a clinician.

Gastroesophageal reflux

The role of the G-tube for children with gastroesophageal reflux is complicated to summarize. [Aumar: 2018]

- Overall there has been a trend away from concurrent anti-reflux surgery, such as fundoplication at the time of G-tube placement, as it is generally not indicated and presents safety and comorbidity risks.

- In one prospective observational study, 74% of children had reflux at the time of G-tube placement, and tube placement did not aggravate reflux in the majority of children. [Aumar: 2018] In this study, 11% of children developed GERD after G-tube placement, and 16% of the patients required anti-reflux surgery at a later time. [Aumar: 2018]

- Medical management is often sufficient to control reflux symptoms in tube-fed children rather than anti-reflux surgery.

- Transpyloric feeding via a jejunostomy or GJ-tube may decrease reflux symptoms but has its limitations, including slower, continuous feeding via pump and the need for imaging to replace the tube.

Role of the Medical Home

While most caregivers report "general satisfaction" with having had a feeding tube placed, many report the need to develop complex coping strategies over the first months to manage the equipment, feeding schedules, and care in addition to other parental responsibilities. The medical home provider is critical to helping with this process by:

- Facilitating family coping strategies

- Adjusting the child's diet for optimal growth and nutrition (and prevention of obesity)

- Adjusting the child's feeding schedule for optimal family/child functioning

- Monitoring the feeding tube for complications (feeding intolerance, reflux with aspiration, stoma leakage)

- Ensuring that the family has adequate equipment for using and caring for the feeding tube

- Ensuring that the family is aware of what to do if the tube dislodges

- Working with the family to ensure adequate and safe feeding during school, childcare, and respite care

- Helping the child and family continue to focus on advancing oral feeding by monitoring safety, prescribing oral motor therapy (if indicated), and optimizing the feeding schedule to enhance hunger during mealtimes

Resources

Information & Support

For Professionals

Enteral Nutrition Handbook, 2nd Edition (ASPEN)

Updated and expanded in 2019 to deliver the best of evidence-based recommendations, practical application, and hands-on clinical skills along with the foundational science that underpins enteral nutrition. Available for a fee from American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.

Nutrition, 3rd Edition (Bright Futures)

Nutrition Issues and Concerns (Chapter 2) provides detailed guidance on breastfeeding and nutritional issues for children with special health care needs. It includes a table with energy calculations for children and adolescents with Down syndrome, spina bifida, Prader-Willi syndrome, cystic fibrosis, and pediatric HIV infection. Available for no cost as a downloadable PDF or for a fee as a printed book.

For Parents and Patients

Feeding Tube Awareness Foundation

A very comprehensive, parent-focused site offering information about feeding tubes, their use, and troubleshooting. Downloadable Tube Feeding parent guide in English and Spanish.

Nasogastric Tubes Insertion and Feeding (Nationwide Children's Hospital)

Clear how-to info for families about NG-tube placement, feeding your child, and cleaning equipment.

Gastrostomy Tube Home Care (Cincinnati Children's Hospital)

Parent instructions on caring for a gastrostomy tube. Includes cleaning, flushing, giving meds, venting, protecting, and problem-solving.

PEG Tube Home Care Instruction (Boston Children's Hospital)

Parent instructions on caring for a child after having a PEG or MIC-G tube placed.

Gastrostomy Feeding by Syringe (Cincinnati Children's Hospital)

Instructions and safety tips for gastrostomy feeding for parents. Also available in Spanish.

Gastrostomy-Jejunostomy Tubes (Cincinnati Children's Hospital)

Includes information about flushing, protecting, adding medications, and solving problems related to gastrostomy-jejunostomy (G-J) tubes.

Services for Patients & Families in Utah (UT)

| Service Categories | # of providers* in: | UT | NW | Other states (5) (show) | | MT | NM | NV | OH | RI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition Assessment Services | 7 | 1 | 3 | 2 | ||||||

| Pediatric Feeding Disorders Programs | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Pediatric Gastroenterology | 4 | 1 | 15 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 19 | |||

| Pediatric Surgery | 44 | 9 | 47 | 9 | 45 | 9 | 46 | |||

For services not listed above, browse our Services categories or search our database.

* number of provider listings may vary by how states categorize services, whether providers are listed by organization or individual, how services are organized in the state, and other factors; Nationwide (NW) providers are generally limited to web-based services, provider locator services, and organizations that serve children from across the nation.

Helpful Articles

Braegger C, Decsi T, Dias JA, Hartman C, Kolacek S, Koletzko B, Koletzko S, Mihatsch W, Moreno L, Puntis J, Shamir R, Szajewska H, Turck D, van Goudoever J.

Practical approach to paediatric enteral nutrition: a comment by the ESPGHAN committee on nutrition.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51(1):110-22. PubMed abstract

Page Bibliography

Adams RC, Elias ER.

Nonoral feeding for children and youth with developmental or acquired disabilities.

Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):e1745-62. PubMed abstract

Aumar M, Lalanne A, Guimber D, Coopman S, Turck D, Michaud L, Gottrand F.

Influence of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Children.

J Pediatr. 2018;197:116-120. PubMed abstract

Dipasquale V, Catena MA, Cardile S, Romano C.

Standard Polymeric Formula Tube Feeding in Neurologically Impaired Children: A Five-Year Retrospective Study.

Nutrients. 2018;10(6). PubMed abstract / Full Text

Dookhoo L, Mahant S, Parra DA, John PR, Amaral JG, Connolly BL.

Peritonitis following percutaneous gastrostomy tube insertions in children.

Pediatr Radiol. 2016;46(10):1444-50. PubMed abstract

Edwards S, Davis AM, Bruce A, Mousa H, Lyman B, Cocjin J, Dean K, Ernst L, Almadhoun O, Hyman P.

Caring for Tube-Fed Children: A Review of Management, Tube Weaning, and Emotional Considerations.

JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;40(5):616-22. PubMed abstract

The purpose of this review is to summarize the multidisciplinary aspects of enteral feeding. The multidisciplinary team consists of a variable combination of an occupational therapist, speech-language pathologist, gastroenterologist, psychologist, nurse, pharmacist, and dietitian.

Friedman JN, Ahmed S, Connolly B, Chait P, Mahant S.

Complications associated with image-guided gastrostomy and gastrojejunostomy tubes in children.

Pediatrics. 2004;114(2):458-61. PubMed abstract

Goday PS, Huh SY, Silverman A, Lukens CT, Dodrill P, Cohen SS, Delaney AL, Feuling MB, Noel RJ, Gisel E, Kenzer A, Kessler DB, Kraus de Camargo O, Browne J, Phalen JA.

Pediatric Feeding Disorder: Consensus Definition and Conceptual Framework.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019;68(1):124-129. PubMed abstract / Full Text

Using the framework of the World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health, a unifying diagnostic term is proposed: "Pediatric Feeding Disorder" (PFD), defined as impaired oral intake that is not age-appropriate, and is associated with medical, nutritional, feeding skill, and/or psychosocial dysfunction. By incorporating associated functional limitations, the proposed diagnostic criteria for PFD should enable practitioners and researchers to better characterize the needs of heterogeneous patient populations, facilitate inclusion of all relevant disciplines in treatment planning, and promote the use of common, precise, terminology necessary to advance clinical practice, research, and health-care policy.

Heyman MB, Harmatz P, Acree M, Wilson L, Moskowitz JT, Ferrando S, Folkman S.

Economic and psychologic costs for maternal caregivers of gastrostomy-dependent children.

J Pediatr. 2004;145(4):511-6. PubMed abstract

Irving SY, Rempel G, Lyman B, Sevilla WMA, Northington L, Guenter P.

Pediatric Nasogastric Tube Placement and Verification: Best Practice Recommendations From the NOVEL Project.

Nutr Clin Pract. 2018;33(6):921-927. PubMed abstract

McSweeney ME, Meleedy-Rey P, Kerr J, Chan Yuen J, Fournier G, Norris K, Larson K, Rosen R.

A Quality Improvement Initiative to Reduce Gastrostomy Tube Placement in Aspirating Patients.

Pediatrics. 2020;145(2). PubMed abstract / Full Text

Morse J, Baird R, Muchantef K, Levesque D, Morinville V, Puligandla PS.

Gastrojejunostomy tube complications - A single center experience and systematic review.

J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52(5):726-733. PubMed abstract

Onwubiko C, Weil BR, Bairdain S, Hall AM, Perkins JM, Thangarajah H, McSweeney ME, Smithers CJ.

Primary laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy tubes as a feeding modality in the pediatric population.

J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52(9):1421-1425. PubMed abstract

Petersen MC, Kedia S, Davis P, Newman L, Temple C.

Eating and feeding are not the same: caregivers' perceptions of gastrostomy feeding for children with cerebral palsy.

Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(9):713-7. PubMed abstract

Sandberg F, Viktorsdóttir MB, Salö M, Stenström P, Arnbjörnsson E.

Comparison of major complications in children after laparoscopy-assisted gastrostomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement: a meta-analysis.

Pediatr Surg Int. 2018;34(12):1321-1327. PubMed abstract / Full Text

Sleigh G, Brocklehurst P.

Gastrostomy feeding in cerebral palsy: a systematic review.

Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(6):534-9. PubMed abstract / Full Text

Sullivan PB, Lambert B, Rose M, Ford-Adams M, Johnson A, Griffiths P.

Prevalence and severity of feeding and nutritional problems in children with neurological impairment: Oxford Feeding Study.

Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42(10):674-80. PubMed abstract

White BR, Ermarth A, Thomas D, Arguinchona O, Presson AP, Ling CY.

Creation of a Standard Model for Tube Feeding at Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Discharge.

JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2020;44(3):491-499. PubMed abstract / Full Text

Source: https://ut.medicalhomeportal.org/clinical-practice/feeding-and-nutrition/feeding-tubes-and-gastrostomies-in-children

0 Response to "When Are Feeding Tubes Given to Children"

Post a Comment